Part 2: Activism and Epidemic

It took many fights and a multitude of twentieth-century environmental disasters for the United States’ present-day environmental protections to be enacted. A commonality across these environmental disasters is that residents of the communities impacted by the disasters had to collectively organize to hold polluters accountable and demand regulatory reform. Fighting through the health ailments caused by those same environmental disasters, residents of these communities helped create a public outcry strong enough that regulatory bodies were made to hold guilty corporate actors accountable.*

These crises would eventually lead to the enactment of major environmental regulatory reforms, most notably the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act in 1980 (CERCLA, also known as the Superfund Program). CERCLA allows the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to craft a master plan to restore a ‘Superfund site’ for pollution sites that exceed minimum thresholds defined in the agency’s Hazard Ranking System (HRS). The HRS is a model in which various characteristics of the site, its wastes, and its surrounding environment are combined through use of a numerical algorithm to compute an overall score.16

Sites that qualify as Superfund sites are placed on the National Priority List (NPL), a designation that initiates a judgement by the EPA of the Potentially Responsible Parties (PRPs) who must bear some or all of the costs of that cleanup.17 As of this writing in June, 2020, there are 1,335 sites actively with this designation across the United States, 31 in Massachusetts.

Among the most impactful — and disturbing — of the environmental disasters that caused these reforms was the Love Canal disaster in Niagara Rivers, New York. It created a moral panic that reverberated nationwide, one which served as a case study for the city of Woburn, which faced its own environmental crisis in the same time period.

The Love Canal Disaster

In 1892, William Love received a permit to excavate the Love Canal, blueprinted to stretch perpendicularly from the upper to lower Niagara Rivers. At the time, canals were thought to be a future mainstay for energy creation, and the Love Canal was blueprinted as a major source of hydroelectric energy for a planned housing development. William Love would only make it as far as digging a mile-long trench before abandoning the project in 1910 for lack of funding.

The canal bed was next used as a dumpsite for both municipal and industrial chemical wastes, until the land was purchased in 1947 by Hooker Chemical, a since-shuttered subsidiary of Occidental Petroleum. With the government’s authorization, Hooker alone began using the partially dug canal as a dump site for chemical wastes produced from their manufacturing processes.18 By 1953, the canal was completely filled back in with 20,000 tons of chemical waste. The following decades would bring horror to the residents of Niagara Falls, New York, both bureaucratically and epidemiologically.

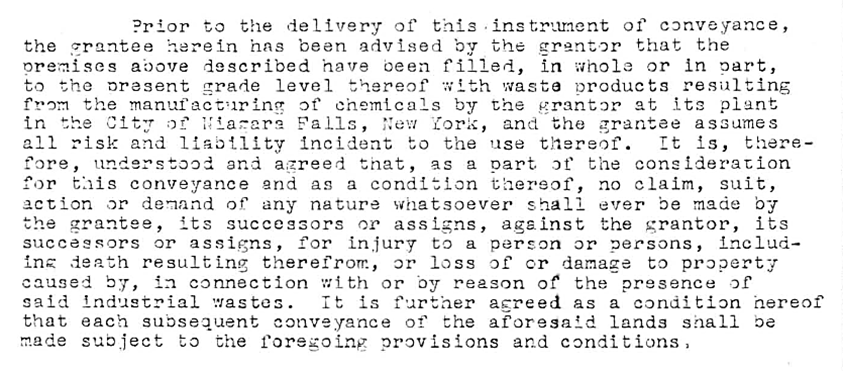

1953 — City developers begin building new residences in the growing surrounding community. The Niagara Falls Board of Education, searching for land to build a new school on, sets their sights on the Love Canal land. Hooker volunteered the site for the bargain basement price of $1.00 (just over $9.50 in 2020 dollars) — provided that the new deedholders sign off on a liability waiver which removed Hooker’s responsibility for any potential injury or death stemming from buried chemical wastes. The Board signed off.

Section of Bill of Sale and Transfer of Property Deed between the Hooker Electrochemical Company and the Board of Education of Niagara Falls, New York, April 28, 1953

Over the next two decades, residents would increasingly report strange odors near the school playground, accumulations of black sludge bleeding through basement walls of the residences along the former Love Canal, and children playing on the school’s playground having sneezing fits and watering eyes. Among these reports—

· 1974 — A couple reports that when they were excavating their backyard for a new pool, the hole they dug immediately filled with rancid blue and yellow liquids. These same chemicals had mixed with the groundwater and flooded the entire yard, reacting so destructively to the redwood posts that one day the fence simply collapsed. When the chemicals receded in the dry weather, the gardens and shrubs looked as though they had been withered and scorched by a brush fire.19

· March 1978 — The New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) opens an investigation, first collecting air and soil tests in basements and then conducting a health study of the 239 families living in residences directly encircling the canal. They find an increase in reproductive problems among women and high levels of chemical contaminants in soil and air20.

· August 1978 — Children living in these homes start to fall ill at an alarmingly frequent rate. Parents organize, demanding that the NYSDOH take action to protect them. The Department ultimately agrees to conduct a more comprehensive investigation, which shows that the contents of the filled-in canal at that point contained over 21,000 tons of toxic chemicals, including at least twelve known carcinogens.21 Among the slurry of carcinogenic chemicals found at the site were benzene, lindane, and trichlorophenol (TCP). But the several hundred pounds of TCP buried in the ground was itself contaminated with Tetrachlorodibenzodioxin or Dioxin for short, known more commonly as Agent Orange — one of the deadliest substances known to man.22

· December 11, 1978 — Seeing that six construction workers are working on a new development near the Love Canal site, residents organize and form an informational picket to warn the workers of the dangers of exposure to Dioxin. Six picketers are arrested for disorderly conduct.

· December 12, 1978 — Several of the aforementioned construction workers are hospitalized for mysterious body rashes.

· August 1979 — Residents begin to leave the neighborhood, citing severe chemical fumes in the area. NYSDOH is mandated to pay food and lodging for 48 hours for families if any family member’s illness was believed causally linked to remedial construction.

· May, 1980 — State University of Buffalo neurologist says some Love Canal residents may have irreversible nerve damage. Frustrated Love Canal residents, upset by the reports, take two EPA officials hostage in the Love Canal Homeowners Association office and hold them for five hours while demanding evacuation of the entire Love Canal neighborhood.23

· July, 1982 — State announces high dioxin levels at the canal. EPA soon confirms that the chemical is present in concentrations 100,000 times that found toxic to laboratory animals.23

An abandoned home bordering the Love Canal site in 1987.7

This environmental disaster had devastating consequences, affecting all aspects of victims’ lives. In 1983 Occidental Chemical, which had bought Hooker, settled $15 billion in claims that had been filed by 1,336 Love Canal residents. It distributed a paltry $20 million lump sum with a $1 million lifetime medical trust to be split by the residents—meaning an average victim received a settlement of $14,250.23

Even if the settlement had been considered acceptable to some victims, they had no way of knowing at the time what the long-term health effects of chronic exposure to carcinogenic chemicals would be.

A 1993 report co-authored by scientists at the Yale University School of Medicine and the New York State Department of Health documented the long-term effects upon residents living near Love Canal and other toxic waste sites.24 Among the 27,000 births by mothers living within 1 mile of New York’s 590 toxic waste sites studied, there was a 12-percent greater chance of giving birth to a child with a major birth defect relative to women living farther from such a site.

90 of the 590 sites were considered to be high-risk locations because there was documented evidence that chemicals had migrated off-site.25 When just these sites were examined, the risk factor soared; women living within one mile of one of these sites were found to have a 63-percent greater chance of bearing a child with a major birth defect relative to women living farther from such a site.

These findings motivated 900 residents to file a follow up suit against Occidental, which resulted in a settlement ranging between $63 to $133,000 in personal injury damages for the victims.23

The disaster served as a case study, though, for communities across the country where residents suspected environmental contamination. Knowledge of the Love Canal case was paramount to the investigations that took place in Woburn, MA just a few years later.

- While this topic is explored throughout The Watershed, exemplary examples of scholarship in environmental justice advocacy include No Safe Place (Brown and Mikkelson), Toxic Communities (Taylor), Water, Place and Equity (Whitely, Ingram, and Perry), Toxic Nation: The Fight to Save Our Communities from Chemical Contamination (Setterberg and Shavelson)

—-