Welcome to The Watershed

Leading up to the June 2019 grand opening of Encore Boston Harbor, neighboring residents had mixed feelings about the resort’s façade. Passersby quoted by Beth Teitell, staff writer for the Boston Globe, shared their impressions for an April 2019 story in the paper. “It’s the same color as the lamp in my grandma’s apartment,” one said. Others likened it to “old union hall brown,” “70s car brown,” and “taupe.”1

The patented ‘Wynn Bronze’ glass abuts the Boston skyline, welcoming inbound commuters on Route 93, one of the main arteries into downtown Boston.

Skyline view of Encore and its surroundings, taken by the author in January 2020

Michael Weaver, the Chief Communications Officer for Wynn Resorts, countered with a multi-part “Well, actually…” defense of the casino’s appearance. He told Teitell that the design was, in fact, iconic enough to be a part of the LEGO Las Vegas architecture set, that “it creates a very warm, inviting glow inside the rooms” and “offers a beautiful reflection of its surroundings at night.”

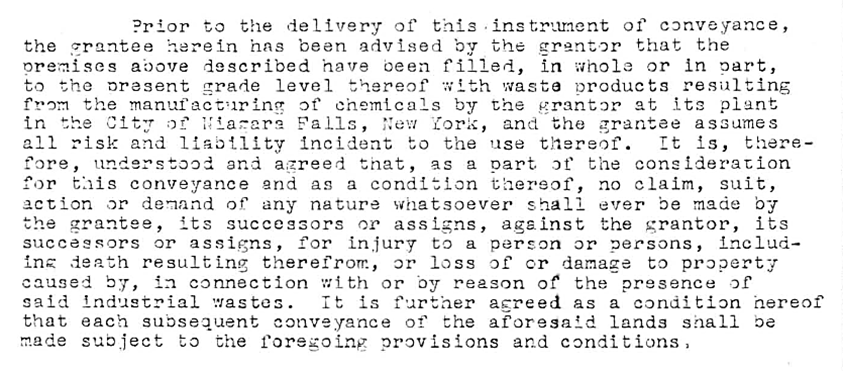

The brand’s vision for the resort was, from the onset, cloaked with altruistic motivations; new, well-paying jobs for service workers from the casino’s neighboring communities, among the most diverse and least affluent in the state. Further injections into the local economy via tourism and tax dollars. And of course, the revitalization of a former toxic waste site reviled by its neighbors for the noxious odors it gave off.

Pre-Project Proposed View of the Casino from the Mystic River, as presented in a 2013 Wynn Resort Expanded Environmental Notification Form2

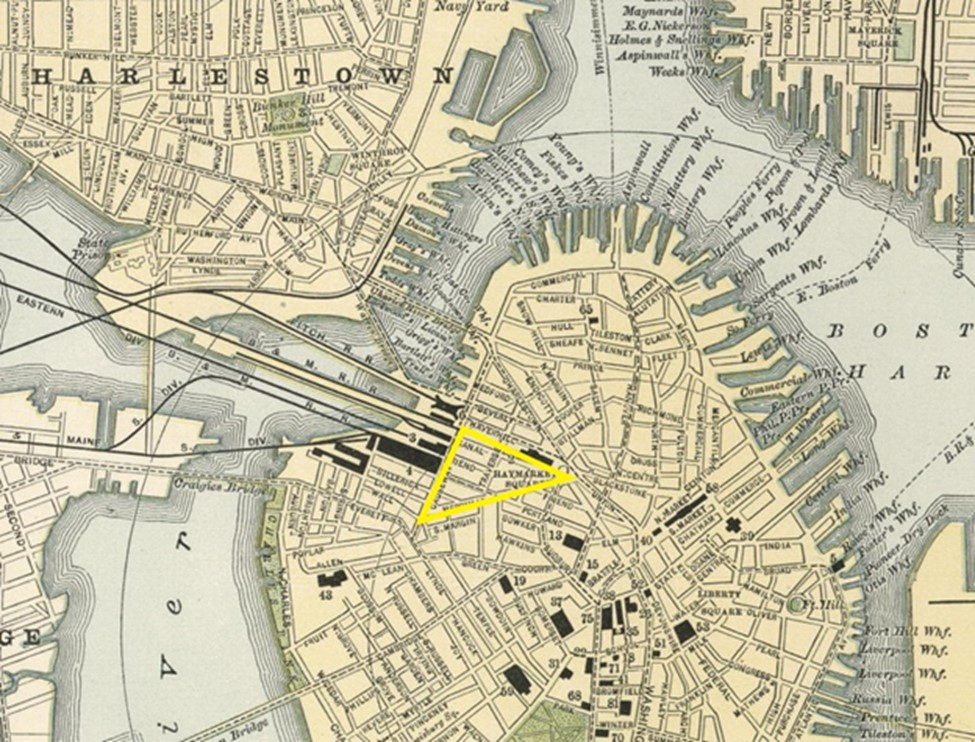

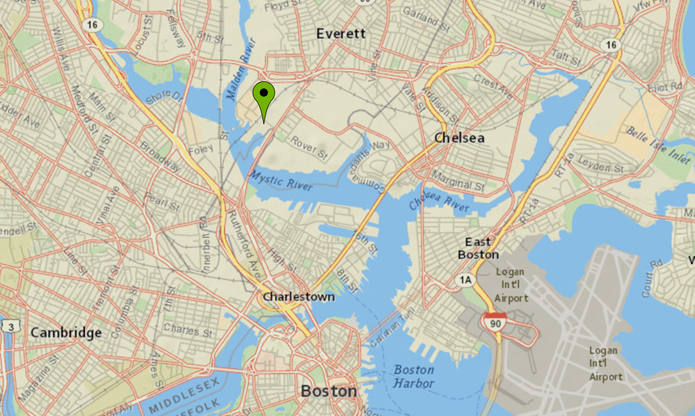

Indeed, this casino resort is built on a plot of land previously occupied by a series of chemical manufacturers, many of whom had a propensity for allowing manufacturing waste biproducts to bleed into the ground and spread into the surrounding communities. Moreover, the site does not exist in isolation — the 34 acres of surface land on which the Wynn casino is built sits adjacent to the confluence of the Mystic River watershed, the Charles River, and the Boston Harbor.

Situated just outside the ostensibly progressive beacon that is Boston, MA, the earth beneath 1 Broadway in Everett, Massachusetts serves as a comprehensive archive of industrialization’s leftovers. What follows is the origin story of some of these subsurface toxins, their ecological consequences felt throughout one of the most populated watersheds in the country, and the primary victims of the resulting environmental injustices — non-white, low income Bostonians. In this regard, this publication is too in part a defense for Weaver’s contentions — Encore Boston Harbor typifies its surroundings.

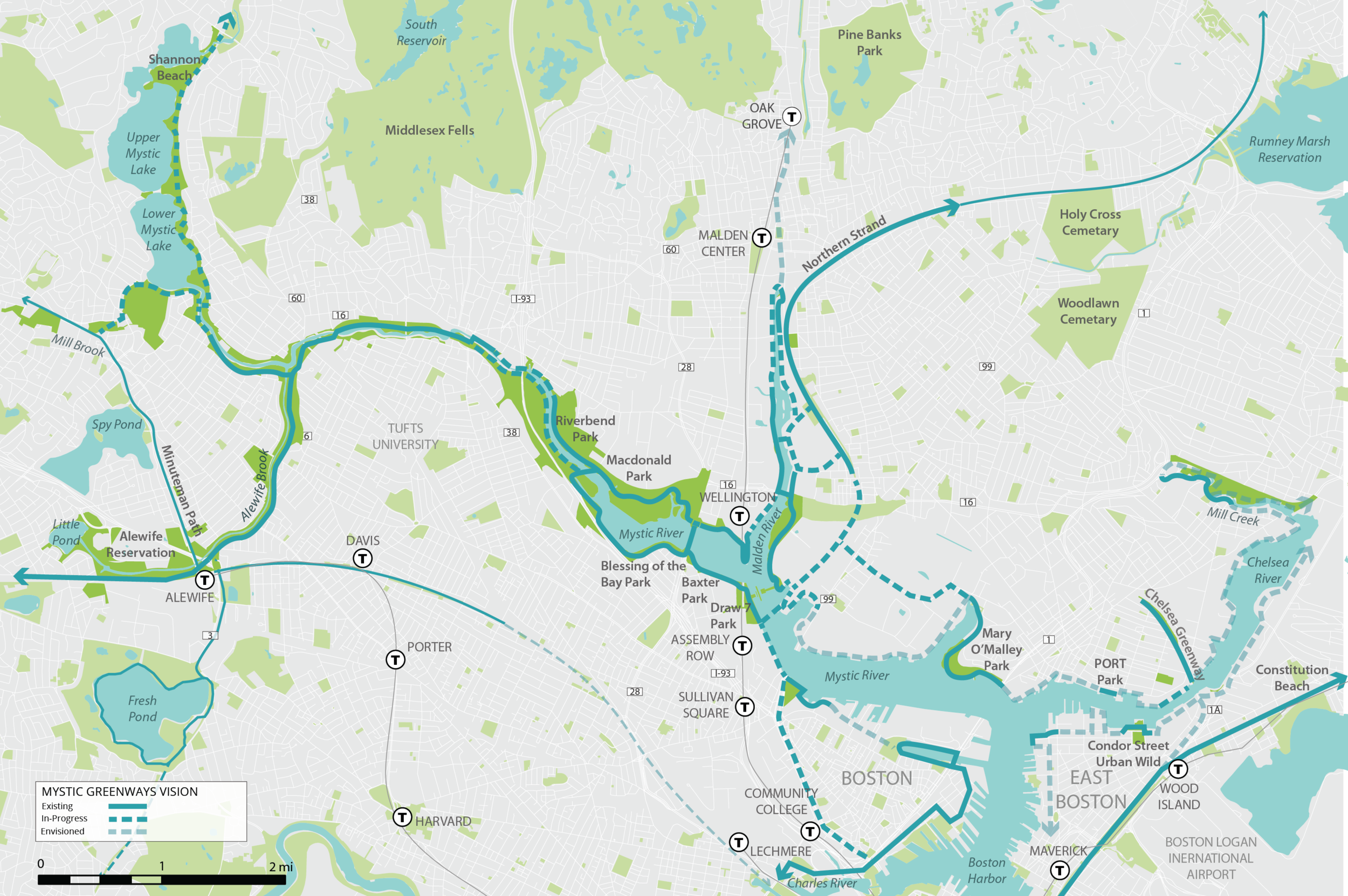

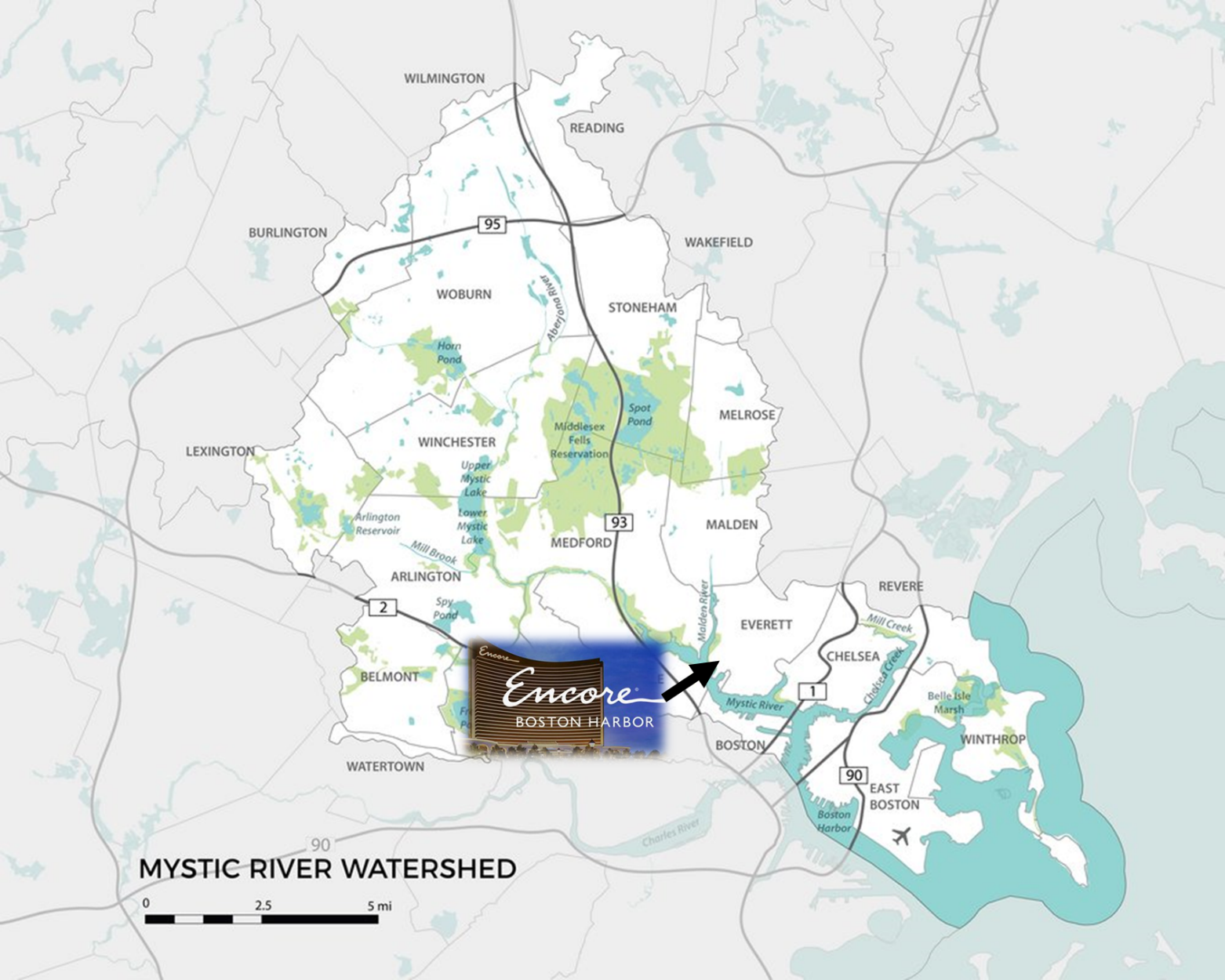

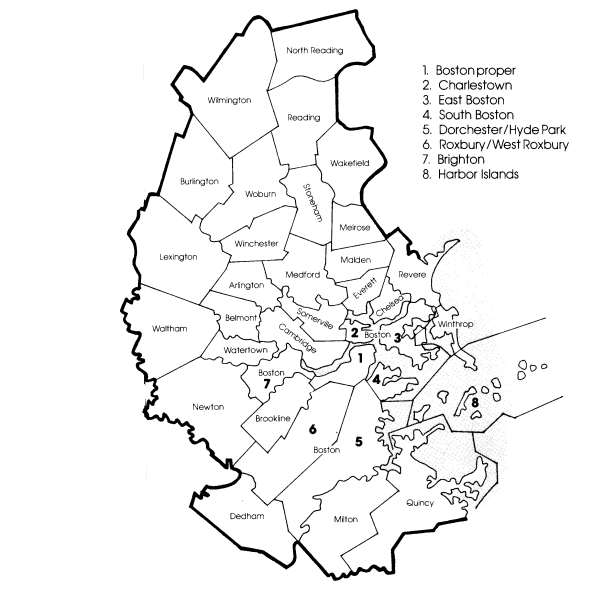

Encore Boston Harbor in Everett, MA within the Mystic River Watershed. Adapted from Mystic River Watershed Association map of Mystic River Watershed, 2019.

The Mystic River Watershed is a distinct land area in Greater Boston. Steven Kolmes, Director of the Environmental Studies Program at the University of Portland, provides a helpful description of the significance of watershed management within developed regions—

Within any geographic region there are areas whose topography determines that they share the same stream and river drainage for precipitation running downhill towards the ocean. Such drainage basins are often referred to as watersheds. Within a watershed a number of distinctive biological communities may exist, as in the common pattern where grassy uplands give way to forested riparian zones along rivers, but these are bound together by a common flow of life's most fundamental molecule... Urban growth challenges watersheds around the world, as mega-cities place huge demands on watersheds that are no longer sufficient to meet increasing needs of growing populations... Watershed level thinking is crucial, as the consequences of alterations to one part of a watershed will inevitably reverberate throughout the rest of the watershed.3

I have organized The Watershed by both geography (north to south) and by social justice construct, as these topics are inextricably linked. The twenty-two communities that are partly or wholly a part of the watershed have remarkable variability between one another with regard to their residents’ income, race, language, and religion. These disparities align disturbingly with the ecological distinctions of the communities, as well as the expected long-term health of their residents. With the outflow of the Mystic River Watershed positioned at its southern end, the accumulation of biochemical waste is most noticeable in the cities closest to the harbor—for citizens with the fewest alternative living options available to them.

Towns and Cities of Greater Boston4

There are avenues to work towards building a more equitable home for all residents of the Watershed. These residents include all humans, but also all other life along the Mystic River. To create a sustainable, humane future for everyone, it is critical to examine the consequences of our collective histories.

Green Marker for Encore Casino in Everett, MA.5