Part 4: Winchester

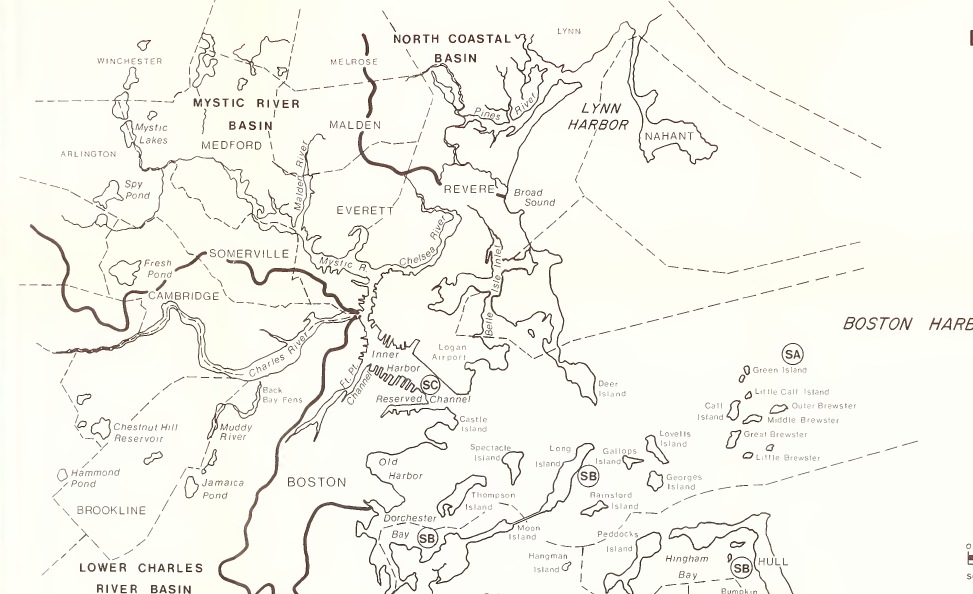

Winchester, MA show in the top left of the Mystic River Watershed.61

Winchester is situated directly south of Woburn, and the Aberjona River likewise flows southward from Woburn through Winchester toward the Mystic Lakes. Renown by early settlers for its natural beauty, Winchester’s early economic development largely hinged upon mills along the lotic water of the Aberjona. The Aberjona River, which is now centuries removed from being safe to swim in, is a center feature in the city’s well documented past.

While tangential from the topic at hand, I feel compelled to share witht the reader one of the more noteworthy stories about the Aberjona River, as described in the 1936 History of Winchester, published by the town themselves— “There ought somewhere to be recorded the sad story of Tufts Richardson, a descendant of Ezekiel, who met his end by drowning himself in the Aberjona on November 16, 1826. Hardly six months before, the young man had taken unto himself a wife with whom, however, he seems to have lived unhappily. We have it on the authority of his kinsman, Nathaniel A. Richardson, who was a small boy when the suicide occurred, that its cause was this: Tufts’ wife Mary had baked a number of loaves of brown bread, some of which turned sour before they were eaten. The young wife told her husband he must eat them up before any more loaves were baked. He refused; she insisted. In the end rather than eat the sour bread the harassed husband went out and threw himself into the river —perhaps the only case where a man carried his criticism of his bride’s cooking to so desperate a length.”62

Winchester, like Woburn, was dominated by leather tanneries and machinery manufacturers in the 19th century. Indeed, the Beggs & Cobb Tannery in Winchester was purported to be the largest tannery of upper leather in the world by the late 1890s.4

A 2017 report written by historian Ellen Knight for the town of Winchester chronologued the history of industrial development along the Aberjona.63 In it, Knight showcased quotes from early 20th century town planning documents regarding water quality along the Aberjona—

1911: “*River channel at Manchester Field was shallow because of material washing into the stream, and the original river channel…Along the shore were many dead eels, and the river was covered with scum at several points. Many street drains emptied into the river. The channels around the islands were almost filled with accumulations of street washings.*”

Exterior of Algonquin Tannery on Abjerona River from 1922 Mass. Fish & Wildlife report32

1928, Judkins Pond (aka Black Ball Pond) ‘is a shallow flowed area, nearly dry in the summer months. … All about the Pond cat tails and other growths hold water in puddles forth propagation of the mosquitoes’ …

*‘Judkins Pond…some fifteen acres are covered to a depth estimated at sixty feet, with a liquid of about the consistency and appearance of black bean soup.’*

At the northwest end was an ash dump. In the summer the pond could be nearly dry.

1928, Cranberry Bog conservation area: Above the cranberry bog the land is low, with a dug canal overflowing at spots into the original Aberjona River bed. Beyond the town line is the Atlantic Gelatin Company Works, with its large area of settling beds and piles of waste material. This deposit must have accumulated for years; the whole hillside and low-dyked areas are covered with the lime-colored, sticky mess, the land appears to be saturated and evidently seeps into the Aberjona River and is washed out in time of heavy rain.

Photo of surveyors from a 1922 Mass. Fish & Wildlife study of Aberjona River Pollution32

1932, Leonard Pond [now Leonard Field]: Across the river, the J. O. Whitten Co. Gelatin Works was ‘dumping sludge refuse upon their property, near the margin of the stream.’

Located at 50 Cross St., the McLetchy Japanning Factory, was ‘also dumping wastes upon the low, wet areas.’

Park commissioners announce plans that ‘In place of swamp lands and mosquito-breeding marshes, there will be attractive self-draining park lands, with ponds that will be suitable for bathing and canoeing in summer and skating in winter.’

1935, Leonard Pond: Aforementioned beach closed. The metropolitan sewer frequently overflowed into the river, which originally fed the pool. The state Board of Health closed the pool.

1938, Leonard Pond: The swimming area is cleaned out by pumping out the water, removing two to four feet of sewerage sludge and mud, and spreading out clean sand.

1953, Leonard Pond: [Swimming area] closed due to pollution, apparently from the state sewer line.

1955, Aberjona River during Hurricane Diane: *The Water and Sewer Department worked until Sunday night on sewers which were overtaxed because people had opened sewer caps to drain cellars. In violation of the law, uncapping of sewers filled Winchester’s mains with more water than they could handle. Some people were shocked when they pulled open sewer caps and sewage water began running into their basements*.

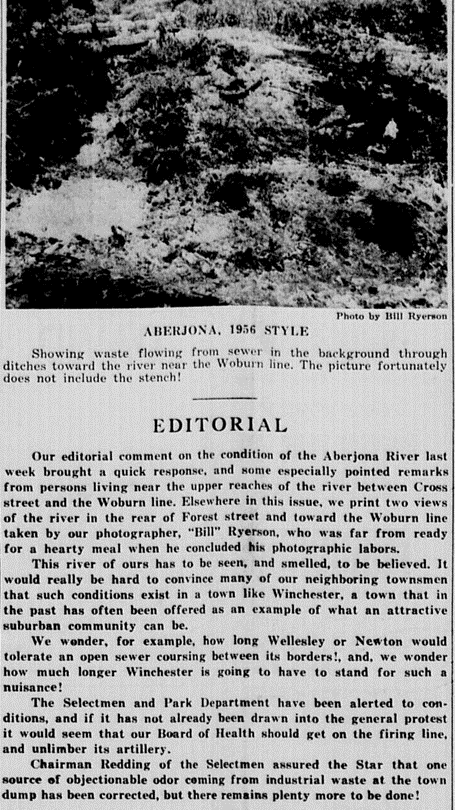

“This river of ours has to be seen, and smelled, to be believed.”

Winchester Star, June 22, 195663

1986, Leonard Pond: Swimming area pumped dry, cleaned, and provided with new sand; reportedly it had the 'clearest water in many years.'

1990, Leonard Pond: Closed for swimming permanently.62

By the second half of the 20th century, Winchester began transforming into a disproportionately affluent community, due in large part to easier highway transportation to and from the city. A 1982 report published by the Massachusetts Historical Commission explained—

Here too, residential development was primarily responsible for the expansion. In this case, however, greater affluence resulted in the construction of mostly single-family houses. In towns like Milton, Newton and Winchester, neighborhoods of fashionable, and occasionally pretentious, houses grew up. Around these developed small commercial centers, country clubs and other middle-class support services.

In the outer suburban areas of Boston's regional core, residential development was characterized by greater affluence and lower density than housing in the inner suburban areas… This kind of affluent development took place in towns like Milton, Brookline, Newton, Belmont, Winchester and Winthrop.4

On the consequences of the societal shift towards suburban living, the Commission’s report continued—

In the same way that automobiles modified public recreational interests, they began to re-orient settlement. Particularly with construction of entirely new highway systems, such as Route 128, industrial as well as commercial and residential development became feasible, even attractive, in areas that previously had experienced little or no development interest. It would require several decades before the full implications of this shift became evident.4

Today, Winchester is known more for its ornate residences throughout the town than for its history as a major manufacturing hub.

Households in Winchester, MA had a median annual income of $152,196 in 2017,64 which is more than the median annual income of $60,336 across the entire United States. 99% of the population of Winchester, MA has health coverage, with 72.5% on employee plans, and 3.35% on Medicaid. 83% of its residents are white alone and 12% are Asian alone.64