Part 6: The Sub-Basin

To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships. - W.E.B. Du Bois71

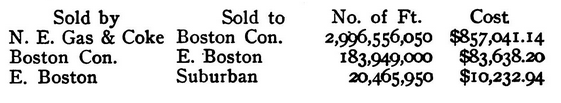

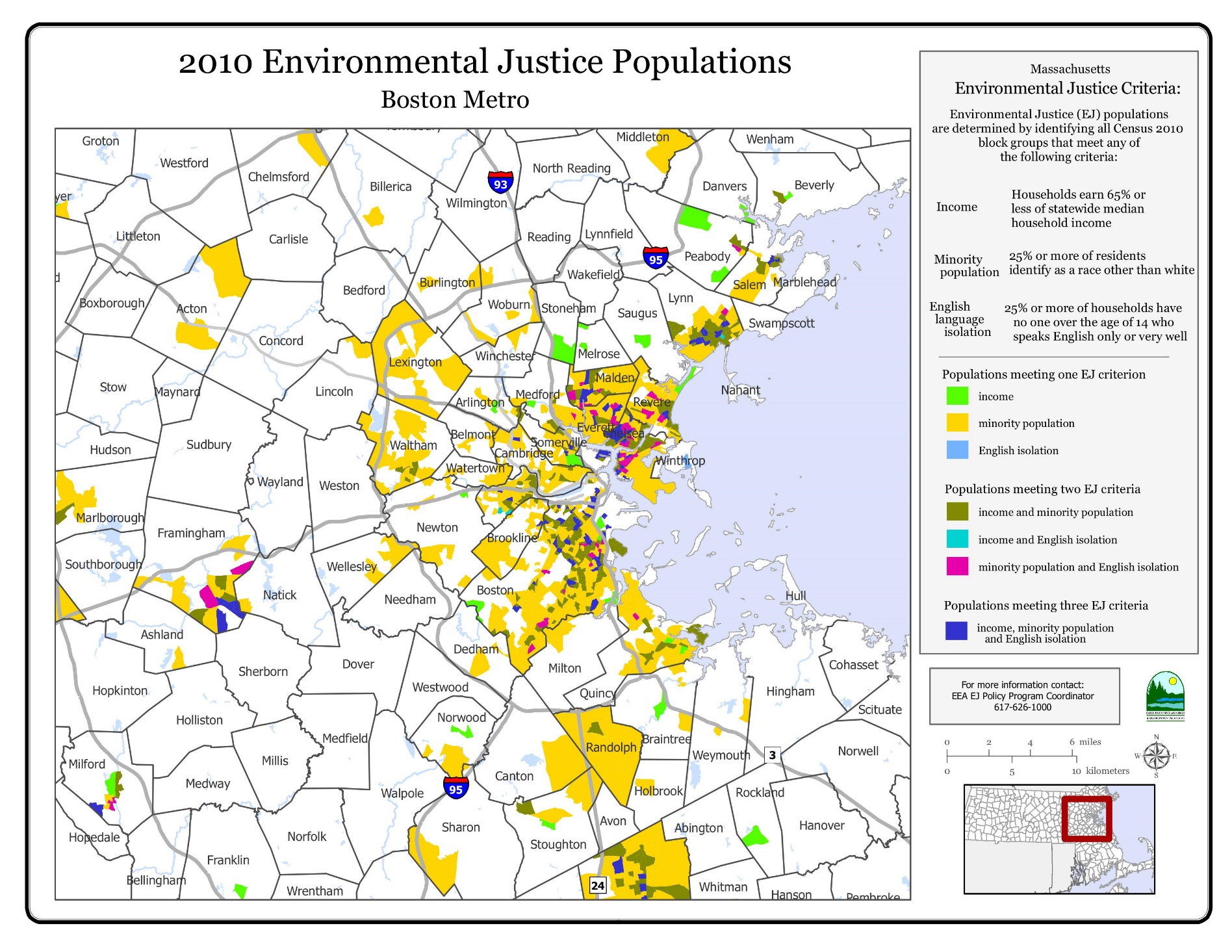

The Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy And Environmental Affairs (EEOEA) produces mapped data sets that correlate US Census Demographic data with Massachusetts communities. The EEOEA established a criterion by which to group ‘Environmental Justice Populations’ if any of the following are true:

- Annual median household income is equal to or less than 65 percent of the statewide median ($62,072 in 2010); or

- 25% or more of the residents identify as a race other than white; or

- 25% or more of households have no one over the age of 14 who speaks English only or very well (“English Isolation”)

As shown in the map below, these classifications are quite widespread within the region surrounding Encore Boston Harbor.

Adapted by the author from Google Earth, 2019. Data on populations from Census 2010 Environmental Justice Populations, superimposed on map using data from the Bureau of Geographic Information (MassGIS), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Executive Office of Technology and Security Services, 2019

The Census Bureau’s 2017 American Community Survey documented that:

- 26.5% of children in Chelsea, MA lived in households with incomes beneath the poverty line, versus just 3.8% in Arlington

- 24% of Everett residents are black, versus less than 1% in Winchester

- More than half of Malden residents speak a language other than English at home, while nearly 80% of Woburn residents speak solely English at home

Drilling specifically into how the communities of Everett and Chelsea relate to other municipalities in the state provides further context. 13.9% of Everett residents live below the poverty line (just $25,465 for a family of two parents and two kids, according to data published by the US Census Bureau), more than 20% higher than the state average. Next door, 19.5% of Chelsea residents live below the poverty line, 75% higher than the state average.72 The correlation between the disproportionately high levels of poverty in these two cities and their racial makeup is the subject of the rest of Part 6.

Everett

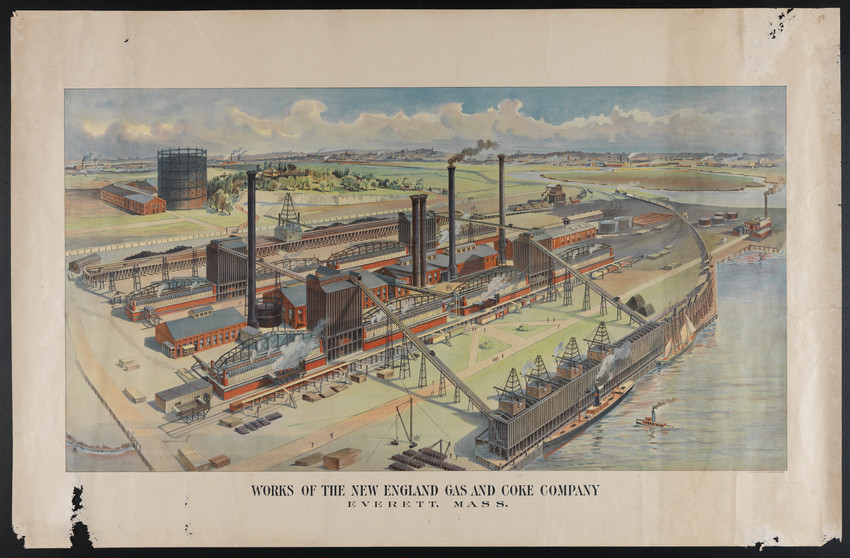

The Encore Resort at 1 Broadway in Everett, MA— however disruptive to the surrounding neighborhoods it may be when operational—is likely among the least disruptive occupants of the land parcel in centuries. As with the Woburn IndustriPlex in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, factories and biochemical plants rapidly expanded in the lower end of the Mystic River.

Large parts of Everett and Chelsea—originally saltmarsh— were transformed by industry and railroads. In contrast to Woburn, these cities had the additional ecological burden brought from being New England’s preeminent shipping and rail terminals. The Massachusetts Historical Commission detailed in a 1982 report—

As the distribution center for much of New England, Boston's waterfront had long been cluttered with wharves and warehouses. During the last half of the nineteenth-century these were joined by vast coal yards which held the reserves required to fuel the railroads, steamships and power generating plants. New technologies required new fuels and by the early twentieth-century, another series of storage facilities, this time for oil, kerosene and other petrochemicals was established. This kind of terminal fringe developed in East and South Boston, Charlestown and Everett.4

Adapted by the author from 1830 map of Boston and adjacent towns, present site of Encore Boston Harbor annotated with star73

The 1912 Historical Register published by the neighboring city of Medford chronologued the evolution of the 1 Broadway plot of land, though Everett had only been incorporated as a city in 1892. The land originated as a part-time island, depending upon the tides. The earliest recorded owner of the parcel was Sam Swan, who had purchased it directly from the town of Charlestown. During low tide, he would pick the vegetation growing on the sandbar and sell it to ‘a man in Reading, for $30 a year.’10

When Swan died in 1825, he bequeathed the land to his son Caleb, who promptly sold the land to the Atwood family the proprietors of the still operational Union Oyster House.74 The Atwoods harvested oysters from the clam beds to supply the restaurant for decades to follow, until railroads and industrial buildings built along the coast polluted the land irrecoverably, eliminating its habitability to oysters. The Historical Register observed—

The island was gradually enlarged until similar filling from the Malden (Everett) shore reached it and the place was an island no longer. At the present time it is thickly covered with factories of various kinds, chemical works, and the accessories of railroad work, all in marked contrast to the days of Dr. Swan.10

The first chemical company along the Mystic was the New England Chemical company. Though it was only operational from 1868 to 1872, many others operationalized shortly thereafter. In 1872, New England Chemical was taken over by the Cochrane Chemical Company.75 Cochrane Chemical grew rapidly in the years that followed, while paving the way for other industrial sectors to move manufacturing operations to Everett, including paint, varnish, dye, iron, steel, oil, gas, and coke refineries. Merrimac Chemical Co. acquired Cochrane in 1917, which itself was acquired by Monsanto in 1929.75

Like the chemical manufacturers, the oil and gas conglomerates were consolidating rapidly, monopolizing the state’s energy production. In a unique 1916 publication, The Boston Social Survey: An Enquiry Into the Relation Between Financial and Political Affairs in Boston, author Grover Shoholm’s commentary traces the familiar public-private parternship approach to providing public services, and its consequences that have yet to be addressed over a century later. For fear it may otherwise be lost to history, I share this passage in full —

The story of Gas has been long since told. There raged a fierce fight, years ago, but a settlement was effected [sic], and, as usual, the public forgets. The turmoil subsides; headlines flash forth a new murder trial or a divorce or the World's Series or other such more important matters; so the public soon forgets.

Mr. A. C. Burrage, a lawyer once upon a time by no means widely known, discovered in the charter of the Brookline Gas Light Company a provision under which that corporation was empowered to extend its service into Boston.

He called the attention of Henry H. Rogers and the Standard Oil interests to this charter and managed to negotiate a sale of the Brookline company to them. The charter was used as a lever by which these interests forced their way into the control of the gas situation in this city.

Burrage received only a fee of $250,000 for the services he rendered; but coming into the good graces of powerful friends prepared the way for acquiring the fortune which he has gained through mining enterprises. Burrage is now known as a powerful copper magnate.

Of interest today, however, is not the story of the shameless means through which the gas interests gained their ends, but rather the relation of the gas industry to the people of Boston at the present time.

The gas companies in and around Boston are gathered into a group, a holding company, — technically a “voluntary association,'' — which calls itself the Massachusetts Gas Companies.

In 1908 six companies composed the system: Boston Consolidated Gas Co., New England Gas and Coke Co., East Boston Gas Co., Chelsea Gas Light Co., Citizens' Gas Co. of Quincy., New England Coal and Coke Co.

The East Boston and Chelsea companies have since consolidated. In the year 1910 there was included: Newton and Watertown Gas Co.

and the next year the combine included: Federal Coal and Coke Co., Boston Towboat Co.

Now the process is going on of acquiring the stock of: J. B. B. Coal Co.

In addition, the system comprises subsidiary manufacturing companies which utilize the valuable by-products of gas production for making such things as dyes and explosives. In 1910 gas made up two thirds of the net earnings, and coal one third. In 1914 the coal profits had increased to 43.6 per cent, of the net earnings.

This is one of the ways in which the profits of the predominant element, the Boston Consolidated Gas Company, have been hidden through the various subtle devices of higher accounting. The Gas Company buys coal from itself, or rather from one of its brothers. The money is all kept in the family, as it were. In this way the modest little profit fixed by the famous “sliding scale” is held at its proper level.

Only a part of the story is told by the published figures, which show that from 1908 to 1915 the profits of the Boston Consolidated have mounted from year to year until they are now higher by about $300,000. The electric department of its business, which averaged $145,000 a year, was sold to the Edison Electric Illuminating Company on Sept. 1, 1909.

Surrounded by a dozen devices for disposing of its surplus profits, there is but little hope that in accordance with the “sliding scale” agreement a reduction in the price of gas will follow increased earnings. The result of the many ingenious arrangements of these related companies may be seen in the dividend statements which appear from time to time in the financial columns of the daily newspapers:

The Boston Consolidated Gas Company has declared a dividend of 2.5 percent., making 8.5 percent, for the year, as compared with 8 percent, last year. The New England Coal and Coke Company has declared a dividend of 10 percent, and an extra dividend of 10 percent. The Boston Towboat Company has declared a dividend of 12 per cent., as compared with 10 percent, last year. The Federal Coal and Coke Company has declared a dividend of 15 percent, as compared with 10 percent, last year. The East Boston Gas Company has declared a dividend of 2.5 per cent, and an extra of 1 percent., making 11 percent, for the year.

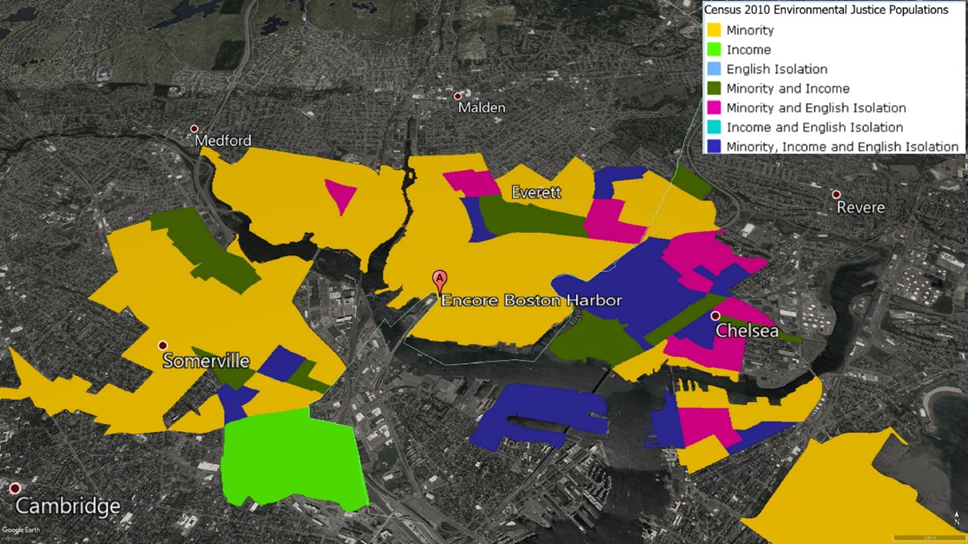

On page 232A of the 1913 report of the Massachusetts Gas Commissioners will be found a schedule showing how much gas the Massachusetts Gas Companies sold to each other and how much they charged each other for it:

According to this table it appears that the New England Gas and Coke Company sold almost 3,000,000 thousand [sic] feet of gas to the Boston Consolidated at 28 cents a thousand; the Boston Consolidated sold 184,000 thousand feet to the East Boston Co. at 45 cents; the East Boston Co. sold 20,000 thousand feet to the Suburban Gas Co. of Revere at 50 cents.

The Massachusetts Gas Companies owns all the above gas companies with the exception of the Suburban Gas Company of Revere. The Massachusetts Gas Companies, therefore, sells its gas three times and makes three profits before it sells to the Revere Company. Then the Suburban sells to the people of Revere at 90 cents.

The gas which is produced at the Everett works of the New England Gas and Coke Company at a cost of about 20 cents finally does reach the consumer, but not until prosperity has been “passed around.”

The timeliness of a little consideration as regards gas is emphasized by the fact that the matter of continuing and extending the “sliding scale” system of gas prices and dividends as at present applied to the Boston Consolidated Gas Company is now before the Legislature.

If this matter played a part in the last election, it was, like other matters of a similar nature, considered only by a small group in the vicinity of State Street; it was not an open campaign issue. Our modern civilization has evolved a wondrous system whereby a business situation, a position of advantage over others, is clinched by means of words printed upon paper. The business strategist has his position given the force of law.

It is around these vantage points of protective law that political battles are waged. With reference to the controlling elements of the political situation, we do not err greatly if we assume that important political struggles are not fought for the sake of the pure spiritual satisfaction of overcoming the wrong and vindicating the right.

There is no important private purpose that cannot be translated into terms of public policy.

It is true, the political parties annually conduct an elaborate form of debate and bring into play all their machinery for producing stage effects of idealism. But in politics words, ideas, disinterested sentiments, have little force.

That the real governing power is the “will of the people,” that government is today maintained and promoted by the general conscience and the general conviction — is a popular myth that would evoke a grin from any experienced campaign manager.76

Drawing of the New England Gas and Coke Company facility, date unknown77

Monsanto had purchased the Everett plant from Merrimac Chemical along with the Woburn plants. Unlike the Woburn facilities which Monsanto sold shortly thereafter, the Everett facility was kept operational from 1929 to 1983. In this period, the industrial sector in Boston saw a marked scale back, as manufacturers relocated their operations to more tax and regulatorily advantageous towns and states, if they did not leave the country altogether in response to union victories for labor protections. The state’s highway system which had been built up in this time allowed for many residents to sprawl outwards from the urban centers. A Boston Historical Commission report explains—

The combination of industrial stagnation, loss of residential population and increased fringe activity brought severe problems to Boston's central core. Among these were abandonment and decay. Most evident around obsolete railroad and water front facilities during the period, these problems were harbingers of more serious difficulties yet to come.4

In 1983, Monsanto sold the plant to Boston Edison. Monsanto specified restrictions on the deed that the land was not suitable for any purpose other than industrial use. Boston Edison sold the property in 1995, and the parcel changed hands several more times after that, with the deed’s use restriction clause being lost along the way.78

Notably, it was also in 1983 that the state enacted the Massachusetts Oil and Hazardous Material Release Prevention and Response Act, which disallowed such omissions.

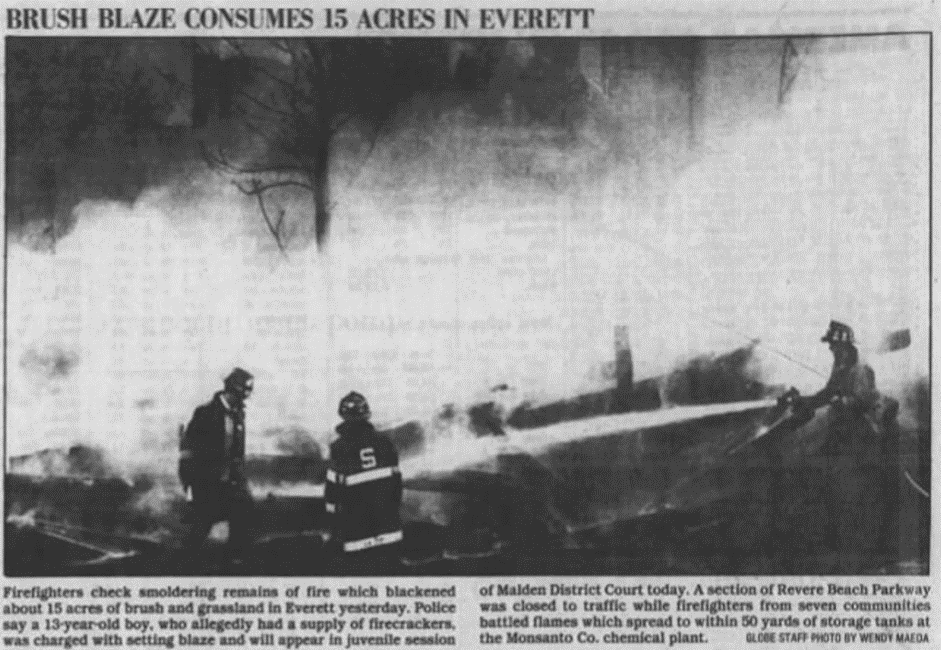

On May 2, 1985, firefighters in Everett, MA responded to reports of a fire in overgrown shrubbery at the site. As a result of the fire, started by a child playing with fireworks, the dense brush throughout the land was partly razed, unearthing fifty to sixty barrels containing a variety of unknown substances.

As outlined in a memorandum by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP), the drums contained one or more of three types of industrial waste — a clear liquid, a white liquid, and a black solid.

The Boston Globe, May 3, 1985

MassDEP’s memo gave an initial conclusion that the clear and white liquids were “most likely a waste byproduct of melamine formaldehyde resin.” Melamine formaldehyde resin, a substance widely used in automotive coatings, epoxy coatings and polyester appliance coatings, emits toxic fumes when exposed to fire, which it would have been from the grass fire.79

The black material, meanwhile, was originally described by Monsanto as ‘roofing tar,’ but it appeared to be quite similar to a substance found buried in a riverbank area adjacent to the plant in June 1984. In that incident, Monsanto removed and disposed of approximately twelve hundred tons of this same black, tarry material, after it was revealed to actually be a mix of toxic chemicals, not simply roofing tar.80

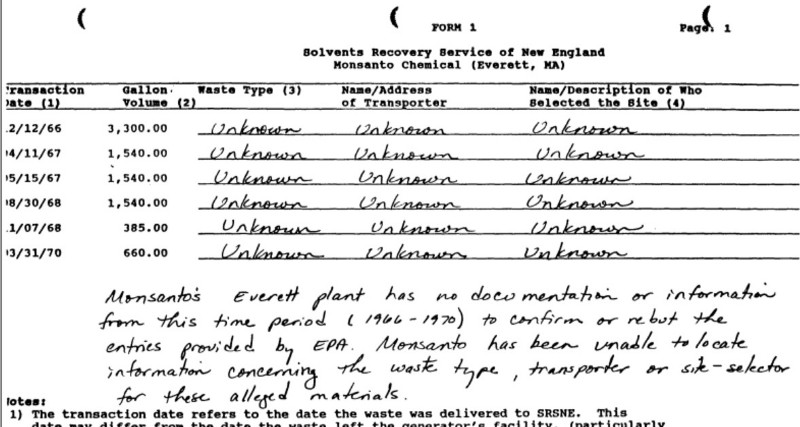

Attempts to identify the chemicals, as well as when they had been deposited into the ground would carry on for years. In their response to an information request in 1992, Monsanto provided an account for the disposal of the wastes,81 which left a bit to be desired—

While Monsanto took the position of not being able to confirm or deny toxic pollution on the site, residents could. One 2014 Boston Globe article recounted an acid leak at the Monsanto plant in 1956, and the hardship it caused residents.82 The Globe reported on other major incidents at the plant in 1951, ’55, ’56, and ’58.

In 1987, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection detected high concentrations of metals and semi-volatile compounds in the soil at the neighboring Massachusetts Public Transit Authority (MBTA) repair facility, which has since been sold to Wynn and been subsumed into the neighboring Encore Boston Harbor property. The MBTA contracted a construction engineering consulting agency to assess the site.83

The investigation, published in 1996, detailed the contaminants and the history of the site. Contamination extended horizontally through the soil beyond the MBTA property, and consisted primarily of metals including lead and mercury.

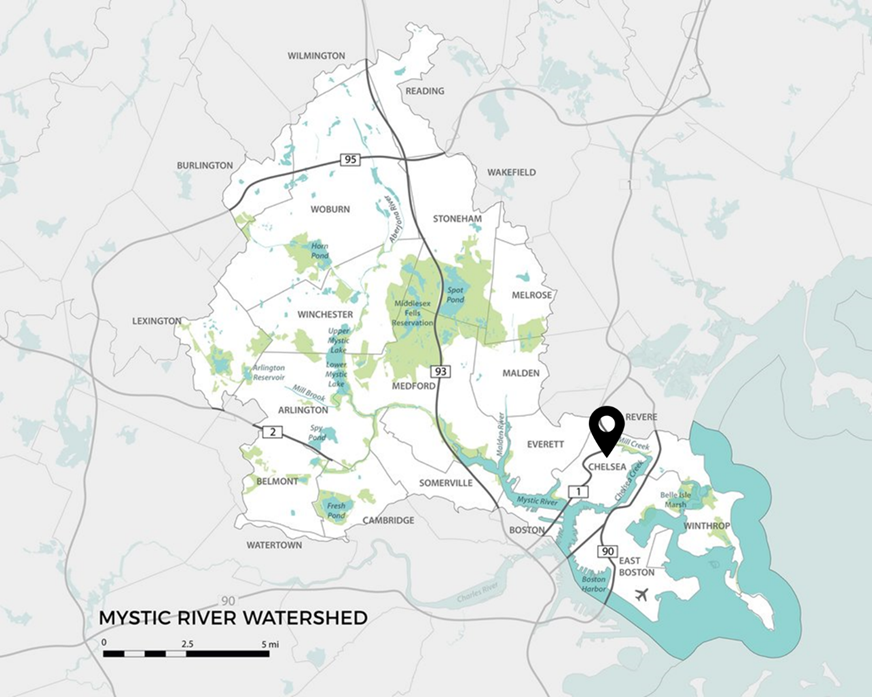

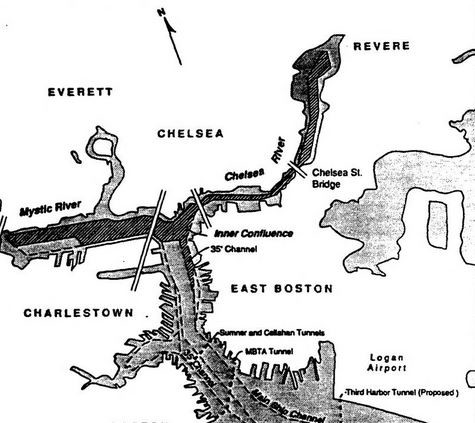

Chelsea, MA within the Mystic River Watershed.84

Chelsea shares much of the same industrious history as Everett, but as the southern end of the Mystic River, it has endured the brunt of accumulated manufacturing waste produced upstream.

Comprising a series of drumlins surrounded by low-lying areas, a sizeable share of the city’s land area was developed by filling salt marshes. Sitting at low elevations, these coastal areas are tidally influenced, with high groundwater tables and poorly draining soil.85

Through the end of the 18th century, Chelsea was primarily farmland; the Chelsea waterfront was a rich source of fish and shellfish, and Chelsea Creek served as a trading post for outgoing vessels.85 By the end of the nineteenth century, Chelsea bore no resemblance to this description. The shipbuilding industry spurred rapid growth in Chelsea’s industrial and transportation infrastructure. Shipbuilding was replaced with the more lucrative leather tanning, manufacturing of rubber, dyes, and varnish, each industries further bolstered by the immense shipping port that the Chelsea waterfront became.

Chalk manufacturer Stickney, Tirrell and Co., picture taken in ~1880 at their plant along Chelsea Creek at the corner of Marginal and Charles streets86

For residents and commuters through the city of Chelsea today, the physical consequences of this unfortunate geographic placement are quite visible to the naked eye.

Indeed, while Chelsea too has a notable history largely defined in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by chemical, leather, rubber, and other industrial manufacturing operations, that history is more familiar to Massachusetts residents. The more inconvenient yet drastically urgent topic of discussion is that of the implicit, stark racial and economic inequities of socioeconomic status and class mobility of Chelsea and Everett, versus that of other communities in the Mystic River Watershed.

Longtime residents of Chelsea have by now grown accustomed to playing the role of ecological waste martyr for the sake of surrounding communities, while themselves having lagging infrastructure for municipal services like sewage treatment.

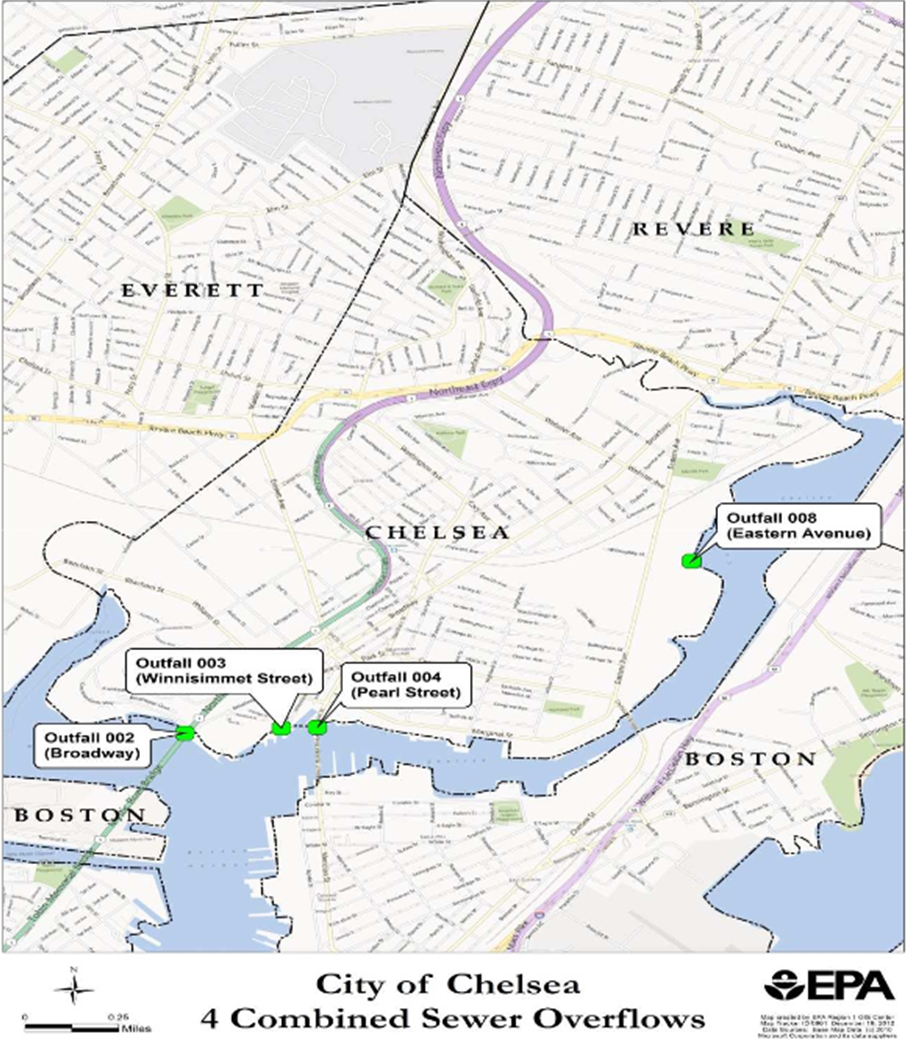

Approximately 70% of Chelsea is serviced by ‘combined sewers,’ designed to collect both wastewater and stormwater runoff in the same pipe. Most of the time, Chelsea’s combined sewers transport all of the wastewater and stormwater to the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority’s (MWRA’s) Deer Island Treatment Plant, where it is treated and then discharged to the Atlantic Ocean. However, during large rainstorms, the combined sewer pipes can exceed capacity. To prevent sewage from backing up into buildings or out of manholes, combined sewer overflow (CSO) systems like Chelsea’s and about 770 other cities across the country have special overflow structures to release the excess wet-weather flow into nearby water bodies.87

Under the federal Clean Water Act, the EPA regulates CSO discharges through the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit program. The EPA allows Chelsea three different locations where, during heavy rainstorms, it may discharge untreated sewage and debris into the Chelsea River. Chelsea’s 2015 annual report of ‘Combined Sewer Overflow’ showed that one of these sites discharged a total of 551,935 gallons, and another released 1,181,189 gallons.88

Chelsea Permitted CSO Locations as of March, 202087

Meanwhile, all of Boston’s Logan Airport’s jet fuel is distributed via Chelsea Creek.89 Seventy to eighty percent of all of New England’s heating fuel is stored along the creek, and over 70 percent of its gasoline and diesel fuel. Road salt for 350 communities in the New England area is too stored along the Chelsea Creek.

The 2019 Chelsea Creek Municipal Harbor Plan documented that—

Chelsea’s industrial activity has resulted in oil and other hazardous material contamination. The Massachusetts General Law, Chapter 21E, also known as the Massachusetts Oil and Hazardous Material Release Prevention Act, is a statute which encompasses issues related to the identification and cleanup of property contaminated by releases of oil and/or hazardous material to the environment.

Under this law, approximately 48% of the land along the Chelsea waterfront in our study area has Activity and Use Limitations (AULs), which signify the presence of known oil and/or hazardous material contamination remaining at that location after a cleanup under the Massachusetts Contingency Plan. These AULs are a result of the current and historic industrial presence in Chelsea.85

More recently, energy company Eversource announced it will build a new substation next to the river. As with Encore Boston Harbor, this project is framed as a public good because it is restoring a contaminated brownfield site into something less societally harmful. As with For a Cleaner Environment in Woburn, the organization GreenRoots has been at the frontlines advocating for the environmental justice of Chelsea residents.

Source: Sjostrom and Leist, 199490

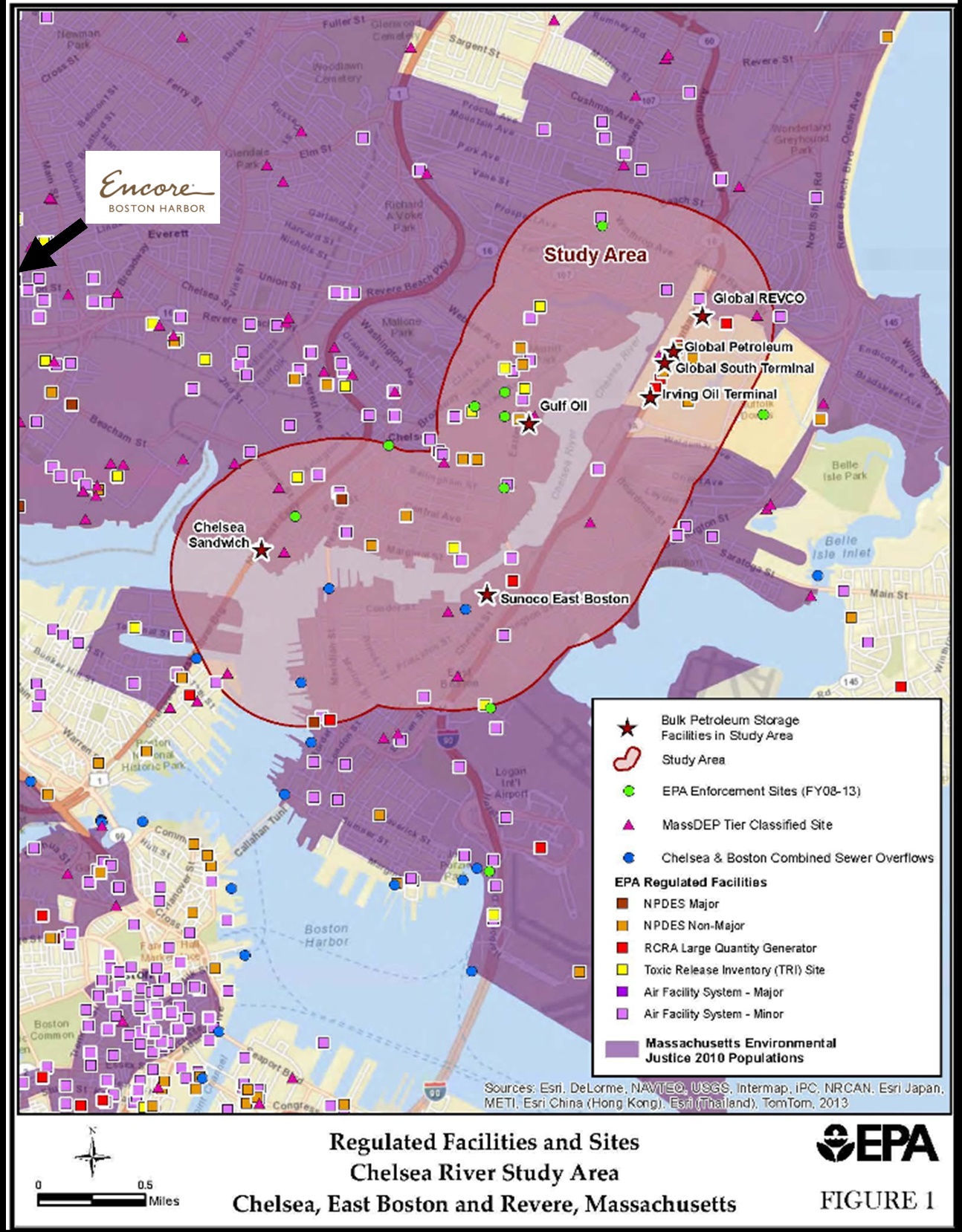

In 1994, a provision was added to the Clean Water Act under “Executive Order 12898.” It dictated that the EPA (as well as all other federal agencies), to the greatest practicable extent, “Make achieving environmental justice part of its mission by identifying and addressing, as appropriate, disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of its programs, policies, and activities on minority populations and low-income populations in the United States.”

In the March of 2014, the EPA conducted an Environmental Justice Analysis under this provision, focused on communities surrounding the seven bulk petroleum storage facilities along the Chelsea River.91

Based on numbers they obtained from the Census Bureau, the report showed that among the study area’s 53,300 residents, 66% were non-white, and 65% primarily spoke a language other than English at home. The report confoundingly concluded that—

Although EPA acknowledges that the Chelsea River and surrounding communities are impacted by many environmental burdens, EPA has determined that the facilities’ discharges will not result in disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects on minority or low-income populations within the meaning of Executive Order 12898.91

EPA map from their 2014 report, highlighting the study area containing facilities storing petroleum products (e.g., gasoline, ethanol, diesel, kerosene, and fuel oil), within a half mile of the Chelsea River, that have been issued National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) surface water permits under the Clean Water Act.91,92

The essence of effective racial discrimination was and remains the creation of rules and circumstances that minimize the necessity for new acts of intentional discrimination. Once such a system has been established, all that is accomplished by forbidding further intentional discrimination is interference with the ability of biased officials to fine-tune the system and adapt it to unforeseen developments.

-Eric Schnapper93

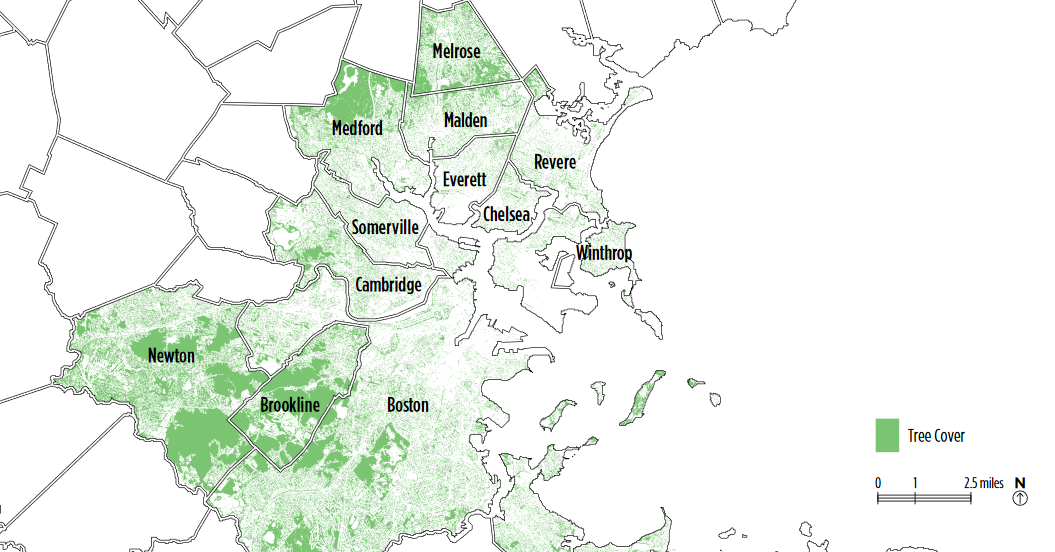

While all of this environmental data on Chelsea’s current state is grim, there are straightforward ways to improve its ecological resources, such as to just replace empty lots with trees. According to the Center for Watershed Protection, the amount of pavement and buildings present in a watershed is a good indicator of the condition of its streams. As coverage by these hard surfaces increases, stream health tends to decline accordingly. In the contiguous U.S., urban impervious surfaces, such as roads, buildings and parking lots, cover 43,000 square miles— an area nearly the size of the State of Ohio.71

Tree Cover in Greater Boston as of 2018 94

Tree planting, though, does not solve for city’s immense racial inequalities. While industrial development has continued, data on the health impacts of these industries upon residents continues to demonstrate the disparities.

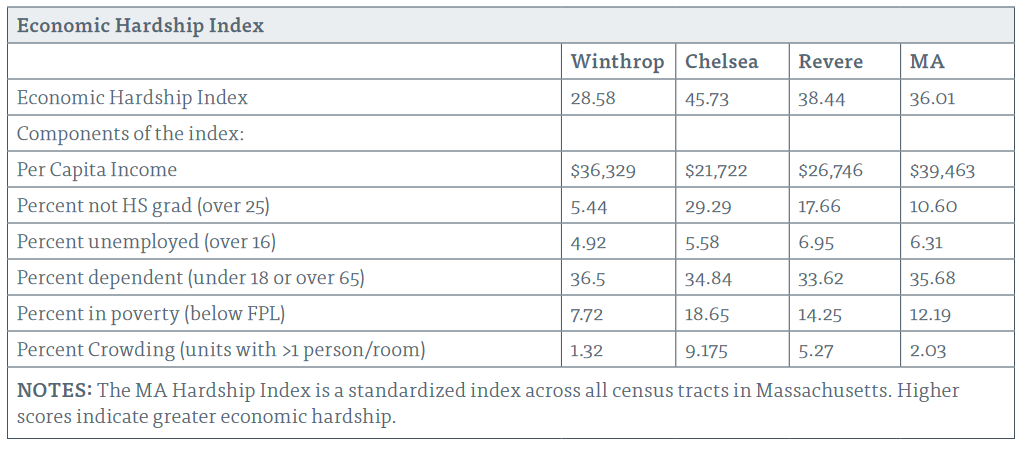

According to an October 2019 report by Mass General Hospital, Chelsea’s age-adjusted mortality rate per 100,000 is 963.8, while that of the state as a whole is 668.9. Twenty-nine percent of children in Chelsea alive below the poverty line, 463 children are homeless, and eviction rates have risen substantially between 2014 and 2016.95

In a survey of Winthrop, Revere, and Chelsea—three of the poorest communities in the Greater Boston region, Chelsea-based community health workers (CHWs) described “slumlords” who do not maintain adequate housing conditions for their tenants. Their patients who are immigrants are reluctant to complain due to their immigration status, thus remaining trapped in substandard conditions.95

2019 Mass General Community Report 95

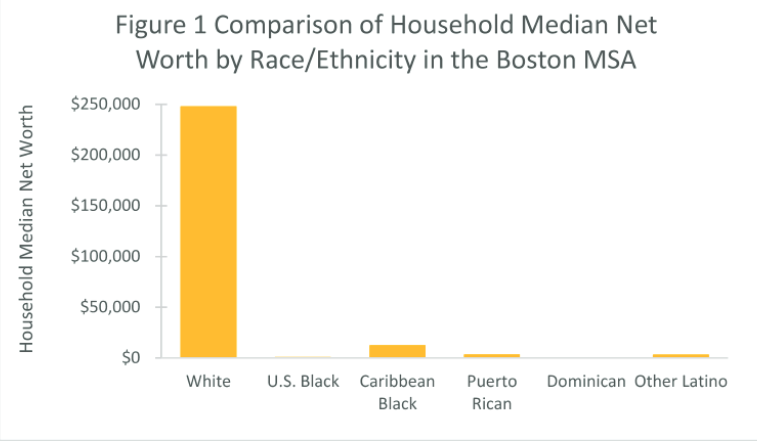

According to the 2012-2016 American Community Survey, Chelsea’s median household income was $49,614.96 This correlates to stark data on median household net worth by race in the Boston Metropolitan Statistical Area (Essex, Middlesex, Norfolk, Plymouth, and Suffolk in Massachusetts; and Rockingham and Strafford New Hampshire).

Comparison of Household Median Net Worth by Race/Ethnicity in the Boston Metropolitan Statistical Area (Essex, Middlesex, Norfolk, Plymouth, and Suffolk in Massachusetts; and Rockingham and Strafford New Hampshire)97,98

From the time of the Articles of Confederation, in each era, in each legislative act, in each political program, we see first a struggle against power on behalf of liberty and then a struggle against liberty, against privatism, against radical atomism on behalf of common goals and public goods that only power can obtain.68

Benjamin Barber

The Path of Least Resistance

While each of the cities within the Mystic River Watershed have a lengthy history of industrial pollution, the extent to which they remain polluted today is largely determined by their proximity to the southern end of The Watershed. There has been a marked decline in the number of companies whose operations produce hazardous waste in the cities that are upriver—Winchester, Woburn, and their neighbors to the north, east, and west. While this divergence is attributable to numerous discrete variables, the divergence in the cities’ racial makeup and household income is attributable to many of those same variables.

The relative absence of their political leverage is at least as significant as the absence of economic power, writes Harvard environmental law scholar Richard Lazarus—

Entities within the federal government with the greatest impact on the give-and-take process that marks environmental protection include the courts, offices within multiple executive branch agencies, and a plethora of congressional committees with over- lapping jurisdiction on environmental matters. Bargains struck in the lawmaking process are expressed in the distributions of the law's benefits and burdens among those interest groups competing for the decisionmakers' attention.

Because legislative and regulatory priorities are established through this lawmaking process, those wielding greater political influence over this process are more likely to have their problems receive ample attention in the first instance. Where the resources required to enact a law or to initiate an enforcement action are especially great, such a political advantage can very well be determinative of how a program's benefits are ultimately distributed. The same is true for allocations of those burdens associated with environmental protection. 99

Shareholder value is maximized when a firm adopts pollution strategies which are not only more economically efficient but that also offer the path of least political resistance. The less political power a community possesses, the fewer resources a community has to defend itself; the lower the level of community awareness and mobilization against potential ecological threats, the more likely they are to experience arduous environmental and human health problems at the hands of business and government. As a result, poorer towns and communities of color suffer an unequal exposure to ecological hazards.100

Economist Harold Barnett writes in his book Toxic Debts about the characteristics of American communities that have been able to adequately address ecological disasters and their residual wastes —

For small, poor, and rural communities, it was less likely even with concentrated benefits. The income, ethnic, and educational characteristics that made these communities attractive sites for hazardous waste facilities also made them less successful advocates for cleanup.60

These are the types of communities disproportionately situated near hazardous waste sites. In the Mystic River Watershed, one’s race is inarguably a strong indicator of their means. Race is correlated to where one can afford live, as it is where they can afford to leave. Where there are those who cannot afford to leave are those who are de facto segregated.