Part 8: Facta, non verba

The Environmental League of Massachusetts, Charles River Watershed Association, Clean Water Action, Conservation Law Foundation, Environment Massachusetts, and Massachusetts Rivers Alliance jointly publish an Energy and Environment Performance Review of each Massachusetts gubernatorial term. Its latest report, published in October 2019 for Republican governor Charlie Baker’s second term, gave an ‘F’ in the Environmental Justice category, ‘D-‘ in the Protecting our Health from Toxic Chemicals category, and ‘D’ in the Solid Waste category.122

It is a luxury to move further away from Superfund sites, and there are immense racial differences in who have that luxury. The pool of Massachusetts residents with the economic means to move further away from toxic waste sites will, of course, generally choose to do so, and those who have that luxury of choice are generally white. This is a contextual phenomenon useful to bear in mind when considering how a state with more than three registered Democrats for every one registered Republican123so frequently elects Republican governors.

When capital is the determinant of an individual’s ability to physically distance their homes from environmental waste sites, any sociodemographic inequalities latent within their communities are ostensibly manifested through the housing segregation which has defined by those inequalities. Racial segregation in Greater Boston is certainly not attributable to this fact alone, but the presence of such waste sites limits reformative measures not involving systemic change.

Without examining the catalysts which create distinct demo-geographic groupings, these causes are merely moved out of one’s line of sight. By rendering nameless and faceless those who are not within one’s same economic class, it is made easier for the wealthy to recede into individualism.

By understanding these differences in opportunity, the consequences of elected leaders’ policies can better be appreciated and legitimized in the ballot box. Critically however, modern conservatism has regressed in its platform’s environmental position to such an extent that legislative compromise on the part of the Democratic party—to the extent that it was ever a prudent strategy—produces built-to-fail bureaucracy.

It is undeniable that Wheeler’s EPA and the Trump administration’s environmental regulation rollbacks are putting the environmental health of countless communities—particularly people of color and those with low-incomes—in tremendous peril. Much of the ecological damage from their regulatory rollbacks will likely be irreversible. But neither of Trump’s two appointees to lead the EPA, nor the Agency’s actions throughout his presidency were particularly anomalous among Republican presidencies since Reagan. And given the past careers of the Party’s EPA administrator appointments, the policies should not have taken any casual observer by surprise. Indeed, many would argue the more damaging dangers to progressive advocacy for environmental justice and ecological protection are found across the aisle.

The post-Reagan era Democratic Party’s presidential platforms have represented Americans’ ostensibly more progressive option, despite never outright rejecting the framing of many Republican positions.

Reagan’s economic policy emphasis on federal deregulation, trickle down taxation, and austerity measures shifted tax burden, regulatory oversight, and financial risk away from high income individuals and corporations onto individuals. The Democratic platform was to undo what the Republicans did. In practice though, the Democrats’ party leaders sought largely to undo the regulatory rollbacks, while embracing the Neoliberal framing of one’s civil liberties as being contingent upon their economic value.

In the years since the enactment of the Superfund, federal environmental regulatory measures have been kneecapped by bureaucratic procedure, the outcome of Congressional compromise between Republican representatives who sought to dismantle oversight altogether and Democrats who sought to maximize their constituents’ economic potential—irrespective of existing systemic inequalities.

Neoliberalism is a constructivist project; it endeavors to create the world it claims already exists. It not only aims to govern society in the name of the economy, but also actively creates institutions that work to naturalize the extension of market rationality to all registers of political and social life. Market rationality—competition, entrepreneurialism, calculation—is thus not presumed by neoliberalism as an innate human quality, but is rather asserted as normative, and as something that must be actively cultivated. The practice of governance in the neoliberalizing regime is precisely to cultivate such market rationality in every realm.

Lisa Brawley124

This indifference to existing, systemic inequalities impedes progress in racial justice. Dr. Dana-ain Davis, professor of urban studies at Queens College and the Director of the Center for the Study of Women and Society, describes the damaging impact of this ‘color-blindness’—

Within this potential erasure neoliberalism plays a perverted race card, in that by rejecting race, formerly racialized ‘‘others’’ can be fully incorporated as consumptive citizens with no racial barriers to their participation in the economy. Neoliberalism, then, willfully misconstrues and dismisses the reality of racism as a powerful explanatory factor in analyzing persistent racial inequities.

This is a rather uncomfortable deflection in the welfare and post-welfare reform era as racism and racial disparities are not easily indicted as racist, the implication being that people suffer no particular harm. Under neoliberal racism the relevance of the raced subject, racial identity and racism is subsumed under the auspices of meritocracy. For in a neoliberal society, individuals are supposedly freed from identity and operate under the limiting assumption that hard work will be rewarded if the game is played according to the rules. Consequently, any impediments to success are attributed to personal flaws. This attribution affirms notions of neutrality and silences claims of racializing and racism.125

These surface-deep policy positions have come to define the Democratic party-approved resistance to Republican policy. As political scientist Adolph Reed Jr. points out—

Why does this tailing behind an increasingly right-of-center Democratic Party persist in the absence of any apparent payoff? There has nearly always been a qualifying excuse: Republicans control the White House; they control Congress; they’re strong enough to block progressive initiatives even if they don’t control either the executive or the legislative branch. Thus have the faithful been able to take comfort in the circular self-evidence of their conviction. Each undesirable act by a Republican administration is eo ipso evidence that if the Democratic candidate had won, things would have been much better. When Democrats have been in office, the imagined omnipresent threat from the Republican bugbear remains a fatal constraint on action and a pretext for suppressing criticism from the left.126

The Clinton presidency encapsulated today’s Democratic policy positions as they exist on the spectrum defined by corporate conservatives. The 42nd president had a penchant for supporting the sort of policies which would be useful if all Americans looked the same and began with the same quality of life in all respects. Reed, again—

Bill Clinton’s record demonstrates, if anything, the extent of Reaganism’s victory in defining the terms of political debate and the limits of political practice. A recap of some of his administration’s greatest hits should suffice to break through the social amnesia. Clinton ran partly on a pledge of “ending welfare as we know it”; in office he both presided over the termination of the federal government’s sixty-year commitment to provide income support for the poor and effectively ended direct federal provision of low-income housing. In both cases his approach was to transfer federal subsidies — when not simply eliminating them — from impoverished people to employers of low-wage labor, real estate developers, and landlords. He signed into law repressive crime bills that increased the number of federal capital offenses, flooded the prisons, and upheld unjustified and racially discriminatory sentencing disparities for crack and powder cocaine. He pushed NAFTA through over strenuous objections from labor and many congressional Democrats. He temporized on his campaign pledge to pursue labor-law reform that would tilt the playing field back toward workers, until the Republican takeover of Congress in 1995 gave him an excuse not to pursue it at all. He undertook the privatization of Sallie Mae, the Student Loan Marketing Association, thereby fueling the student-debt crisis.

Notwithstanding his administration’s Orwellian folderol about “reinventing government,” his commitment to deficit reduction led to, among other things, extending privatization of the federal meat-inspection program, which shifted responsibility to the meat industry — a reinvention that must have pleased his former Arkansas patron, Tyson Foods, and arguably has left its legacy in the sporadic outbreaks and recalls that suggest deeper, endemic problems of food safety in the United States. His approach to health-care reform, like Barack Obama’s, was built around placating the insurance and pharmaceutical industries, and its failure only intensified the blitzkrieg of for-profit medicine…

It is difficult to imagine that a Republican administration could have been much more successful in advancing Reaganism’s agenda…

But if the left is tied to a Democratic strategy that, at least since the Clinton Administration, tries to win elections by absorbing much of the right’s social vision and agenda, before long the notion of a political left will have no meaning. For all intents and purposes, that is what has occurred. If the right sets the terms of debate for the Democrats, and the Democrats set the terms of debate for the left, then what can it mean to be on the political left? The terms “left” and “progressive”—and in practical usage the latter is only a milquetoast version of the former—now signify a cultural sensibility rather than a reasoned critique of the existing social order. Because only the right proceeds from a clear, practical utopian vision, “left” has come to mean little more than “not right.” 126

Hillary Clinton and then-CEO of Goldman Sachs, Lloyd Blankfein in 2014 127

The US is to an unusual extent a business-run society, where short-term concerns of profit and market share displace rational planning.

Noam Chomsky

Collective Action for Intercommunality

The intersectionality of the issues of a person’s class, race, wealth, and healthcare access are highlighted by the varying hospitalization and mortality rates of different demographics. Relatedly, the influence of capital on so many aspects of American governance is increasingly a competing interest to human life.

Nearly all aspects of American life are defined and circumscribed by the Neoliberal dogma of the accumulation and utilization of wealth within the bounds of market-focused regulation. Critically though, some aspects that American law exists to protect are simply more resilient than others, because their damages cannot be remediated.

The collapse, or subsidence, of land areas resulting from groundwater pumping, is virtually irreversible.128 Carelessness or malfunction when mining lead can result in toxic acid mine drainage into groundwater, a virtually impossible to reverse process.129

Low levels of neonatal, prenatal, or pediatric exposure to lead can quickly cause untreatable, irreversible damage to the brain.130 One’s death attributed to their unwillingness to go to the hospital without health insurance is of course irreversible. Loss of species through damage to habitats, climate change, and poaching is irreversible.

Moreover, the trichloroethylene in Woburn did not care what the human consuming it looked like. Nor did the benzene in the Love Canal, arsenic in the Aberjona, or petroleum in Chelsea Creek. What is the measure of incremental ecological progress on a continuum with an initial baseline of a career coal lobbyist in Andrew Wheeler as the head environmental enforcement? Will climate change bend to, or allow for, incremental regulatory reform?

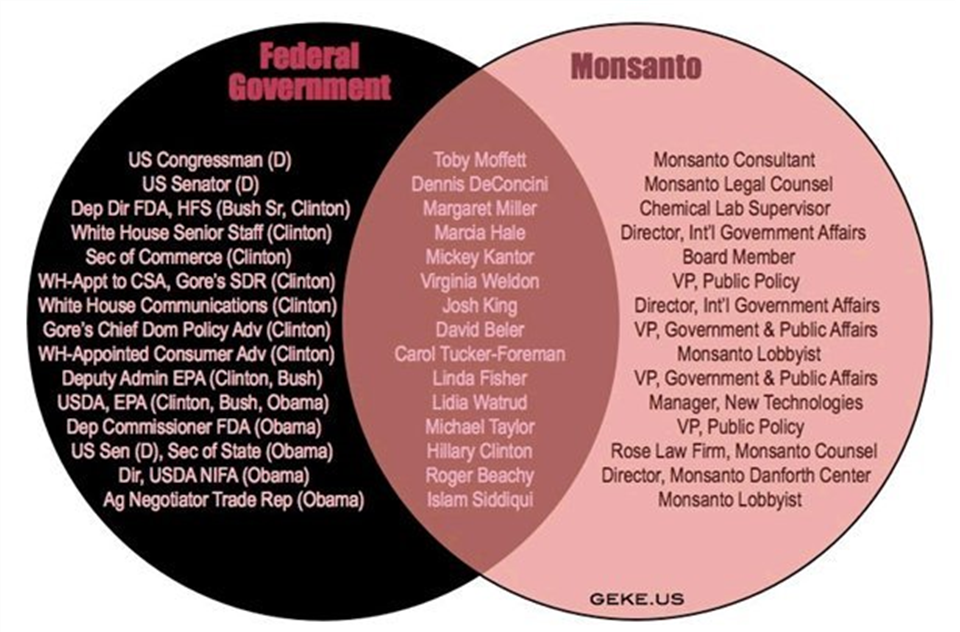

When the establishment political parties and cable news media work in lock step to manufacture consent into the narrow bounds of discourse that exist between a presidential cabinet of lobbyists who spent their careers advocating for the deregulation of the agencies they are appointed to oversee, and an opposition whose cabinets are made up of careerists who only took those lobbyists’ campaign funds, the rate of deterioration of the United States’ air and water quality clearly outpaces policy enactment.

Communities are not affected by environmental destruction homogenously, nor at the same pace. When one side of the argument has so much more to lose which cannot be regained, those on that side of the argument have no reason to ask for mere compromise, nor for incremental change. Many of the existing environmental protections which have originated at the federal level are often only in response to the most conspicuous environmental disasters throughout American history.115

Meanwhile, the influence of corporate contributors and the theme of revolving door regulatory appointments has only increased in the past two decades, with the US Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision opening the flood gates for unlimited corporate expenditures towards voter influence, and the Court’s McCutcheon v FEC decision, removing the cap individuals could contribute overall to federal candidates, parties and PACs during a two-year period.131 Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have been the only two major presidential candidates to buck that trend in recent years.

Source: Stephanie Herman, GEKE.US132

This highlights the critical role played by community organizing, such as that by GreenRoots and the Chelsea Collaborative in Chelsea, by For A Cleaner Environment in Woburn, and the Love Canal Homeowners Association in Niagara Falls, New York. Local action has strongly influenced federal activities, and has the capacity to help define the federal environmental regulatory agenda.

More broadly, Dr. Denis Salles of France’s National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and the Environment (INRAE) presents a further diagnose in his brilliant publication Responsibility-based Environmental Governance—

The progressive withdrawal of the state over the last three decades goes hand in hand with a transfer of responsibility and arbitrage from the state to individuals (user-citizen-consumer) in the name of the governance principles called upon by globalization and the liberalization of commercial exchanges. Following that logic, public authorities would assume the role of prescribing norms, guide individual choices and increasingly control private as well as public choices and their consequence on the collectivity.

Thus, the principle of responsibility and the mechanisms of responsibility transfer observed in the field of the environment, which has become “everybody’s business”, converge with an ideology of autonomy of individuals with respect to socializing institutions and with a discourse on the valorization of self-regulation of individual behavior and the liberating power of the individual’s ability to determine their life-choices.121

Salles offers valuable insights regarding recalibrating governmental institutions to elecit behaviors of equality rather than individualism, and in doing so, better protect the planet from damaging practices—

If the progress of individualism is seen as a historical step in the modernization of societies, and not reduced to a product of neoliberal ideology, but seen as a democratic asset which elevates the social individual equipped with a capacity for reflection, criticism and autonomy, then this leads to an increased political status of individual responsibility. This concept of an active responsibility, rather granted to than burdened upon the individual, brings him to constantly question the meaning of his practices with regards to their intended consequences and to the perverse side effects of their behavior. Responsibility then acts as the ‘moral correction mechanism of individualism. It is the limit beyond which one cannot afford to be purely individualistic… Individualism and society are not contradictory, the contrary is true.’133

The concept of a ‘shared responsibility’ displaces the paradigm of pure domination, which considers responsibility as a consequence of an egoistic or imposed individualism and as a vehicle of neoliberal ideology. Most scientific investigations underline the importance of economic and cultural determinants crucial for the adoption of new social practices less harmful to the environment. The hesitancy to move on to action stems from the difficulty of putting alternative practices into place, such as different transport modes, waste recycling or energy and water savings in an environment ruled by the constraints of the organization of labor, lifestyle and consumption modes. Environmental practices are economically and socially dependent on more immediate needs, for example commuting to the workplace, school or shopping centers. In order to better understand the question of responsibility in the environmental field, it seems preferable to see the different interpretations as complementary, rather than as mutually exclusive, in an open and pluralistic attitude towards the process of responsibility transfer.134

In a hypothetical ecosystem with laws of physics bound by the tenets of a market-based economy, the Mystic River’s water would not flow from Woburn to Winchester to Medford to Everett to Chelsea, as it would respect municipal boundaries. In such an ecosystem, the water that rained on the IndustriPlex would not drain into the Aberjona River’s drainage basin and then into the Mystic River, as it would respect property lines.

If in such an ecosystem there existed an egalitarian society, wherein no person experienced homelessness, faced inordinate social or physical obstacles attributable to the prejudices held by others; where no family drank from a water supply contaminated with carcinogens, endured a barrage of corporate marketing campaigns conveying the subjective as objective, or were governed under regulatory institutions architected to sustain the aforementioned inequalities, then perhaps a society built as ours has been built would suffice.

But amid the economic inequality, accumulated environmental destruction, and racial opportunity disparities found today within the Mystic River Watershed, there is finite time afforded to advocate for something more.

—-